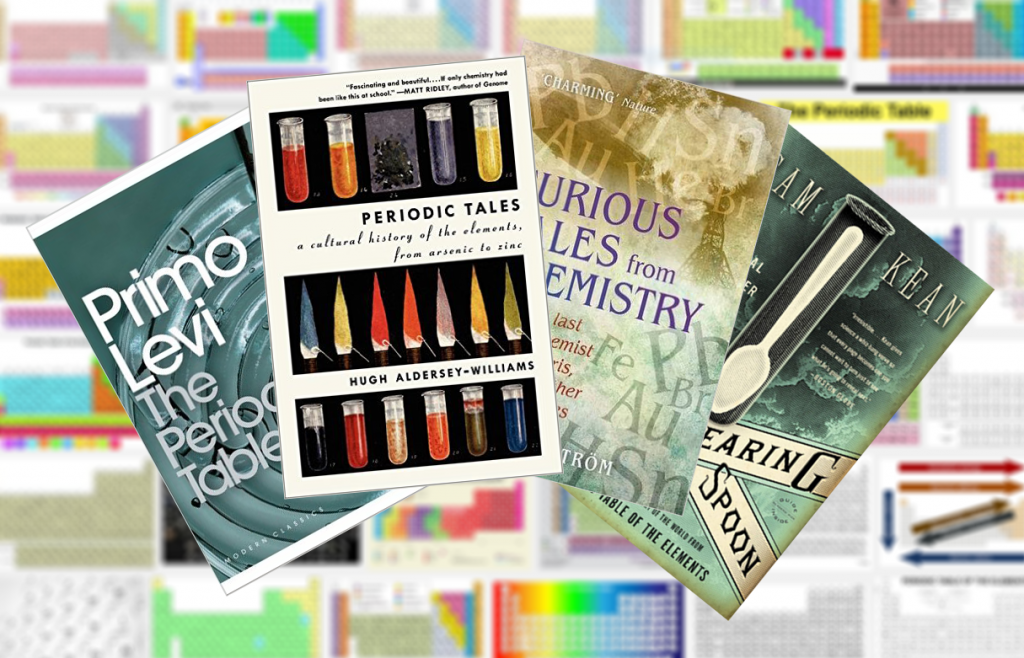

If you’re going to write a book from a collection of anecdotes it helps having a hook to anchor the stories to. And what better hook than the periodic table of elements? I just finished Lars Öhrström’s “The Last Alchemist in Paris: And other curious tales from chemistry” the latest in a trio of books on a similar theme I’ve read recently. The others being “The Disappearing Spoon: And Other True Tales of Madness, Love, and the History of the World from the Periodic Table of the Elements” by Sam Kean and “Periodic Tales: The Curious Lives of the Elements” by Hugh Aldersey-Williams.1

Superficially similar—all collections of short, chemistry-related stories—the three books are very different beasts. The most straight-forward is Kean’s, which in large parts relates the history of the periodic table itself, the elements and the men, and occasional woman, who discovered them. It’s filled of amusing anecdotes, some well-known, some less so, of the type you might over-hear in a science-department lunch room (or, better yet, oven an after-work beer) and ask yourself “can that really be true?”2. The tone is jovial and colloquial to the point of grating. Kean’s insistence on avoiding jargon (i.e. real scientific terms) at any cost makes the text really annoying at times, especially in the section where he tries to explain the function of atomic clocks:

This causes cesium electrons to pop (i.e., jump and crash) and emit photons of light.

By contrast, Aldersey-Williams’ Periodic Tales is a more personal journey through the periodic table. In the prologue he professes that he wishes

to discover the cultural themes that group the elements anew, to draw up the periodic table as if sorted by an anthropologist.

Although Periodic Tales also contain stories of discoveries (sometimes the same as in Disappearing Spoon) Aldersey-William takes us with him through a Dorset kiln, the tin mines of Cornwall and his own efforts to extract phosphorus from pee. In beautiful prose Periodic Tales mixes the elements with history,art and literature. It’s showing us chemistry beyond science and engineering. Of the two, Periodic Tales is clearly the more enjoyable.

Öhrström’s book stands out from the group; here are no discovery-tales or anecdotes about famous scientists. This book is, as the subtitles says, about chemical curiosities, and how these have influenced history and culture. And when it hasn’t; Öhrström thoroughly debunks the infamous tale that tin should have doomed Napoleon’s Russian campaign, an event touched upon with far less scepticism also in Keans book. However, if both Kean and Aldersey-Williams maintain the periodic table as at least a loose thread through their books, Öhrström dispenses with that link. The episodes in The Last Alchemist seems chosen at random without any common theme outside the grand topic of chemistry. The author himself says as much in an article about his writing experience:

The chemistry was to be the firm ground from where I could make fishing expeditions into history for suitable protagonists and where I could anchor up with a set of characters I had already decided upon. Roughly half of the stories that ended up in The Last Alchemist in Paris are there because of a particular chemistry I though needed telling, and the other half because of my particular interests in history, literature and film.

So Öhrström, a professor of chemistry, wants to teach us some of that topic as well, and he doesn’t back away from giving the reader some solid chemical background to the episodes, even if the connection between the chemistry and the curiosity at times is quite tenuous. But the stories are interesting, and, as with Aldersey-Williams, sometimes personal. The majority of them should be new for most readers, and although Öhrström’s style is a bit clunky at times, it’s an eminently readable book.

Nevertheless, in comparison to the grand-daddy of element-themed literature these all fall short. Primo Levi used the elements as a thread to recall the “strong and bitter flavours” of his experience as a chemist just before and during World War II, including how cerium helped him survive in Auschwitz. Levi, to borrow a Polish expression, has the light pen Kean, Öhrström, and, to a lesser degree, Aldersey-Williams lack. The Periodic Table is a haunting book—deeply disturbing, yet with effortless eloquence and beauty. Despite the futility of ranking such a diverse range of literature I’m not going to complain about that the Royal Institution in 2006 named The Periodic Table the best science book ever.

All of the above-mentioned books are worth reading: The Disappearing Spoon is amusing and full of re-tellable tales. The Last Alchemist is perhaps more interesting, at least for readers with some basic chemistry background, for its deeper foundation in chemistry. My favourite of the three is, however, Periodic Tales. The style of writing and the personal approach to the topics appeals to me. But if you haven’t read The Periodic Table it’s an obligatory read.

1 Is there a rule that I’ve missed that non-fiction books are obliged to have a witty title with an explanatory subtitle?

2 And sometimes they aren’t. Kean writes about Linus Pauling (p. 151): “After losing out on DNA, Pauling got a consolation prize: an overdue Nobel of his own, in Chemistry in 1954. […] He even won a second, surprise Nobel Prize in 1962, the Nobel Peace Prize, becoming the only person to win two unshared Nobels. He did, however, share the stage in Stockholm that year with two laureates in medicine or physiology: James Watson and Francis Crick.” But as any Swede knows, the Peace prizes are awarded by the Norwegians (which is why we can claim innocence to some of the more outrageous awards) in Oslo. But not only that: according to the Nobel webpage, the 1962 Peace prize was awarded in 1963! Wilkins, Crick and Watson collected their prizes in 1962.