The story of the chemical fascination of a young boy growing up in London in the 1930s in a large Jewish family flickers in and out between biography and a history of chemistry itself. As a precocious child, Oliver Sachs, under the guidance of the title’s Uncle Tungsten, a lightbulb manufacturer1 with a passion for heavy metals, his other Uncle Abe and a voracious appetite for Victorian chemistry books, develops a passion for chemistry that leads him to set up a small lab in his family house and himself recreated many of the experiments that distilled chemistry out of the crucible of alchemy.

As in Primo Levi’s The Periodic Table, the author’s family story and the properties of the elements, their history and the development of chemistry itself, from Lavoiser to radioactivity, intertwines and blends into a single narrative.

As for young Sachs himself, he seems unbelievably mature; setting up his own lab, taking up photography, dissecting animals, and much more. All at the age of nine to twelve – during the second world war. He has far more hands on experience as a chemists at the age of ten than I have running a chemistry group at four times his age. From immersing himself in the periodic table, Sachs convinces himself that uranium cannot be in the tungsten group. After the war, when the secrecy of radioactivity is lifted, he is happy to see his suspicions confirmed. But then, seemingly destined for a future in chemistry, he gives it all up. Why? Sachs seems unable to provide an answer. In the final paragraph he writes:

Was it the inevitable course, the natural history, of enthusiasm, that it burns hotly, brightly, like a star, for a while, and then, exhausting itself, gutters out, is gone? […] Or was it, perhaps, more simply, that I was growing up, and that “growing up” makes one forget the lyrical, mystical perceptions of childhood, the glory and the freshness of which Wordsworth wrote, so that they fade into the light of common day.

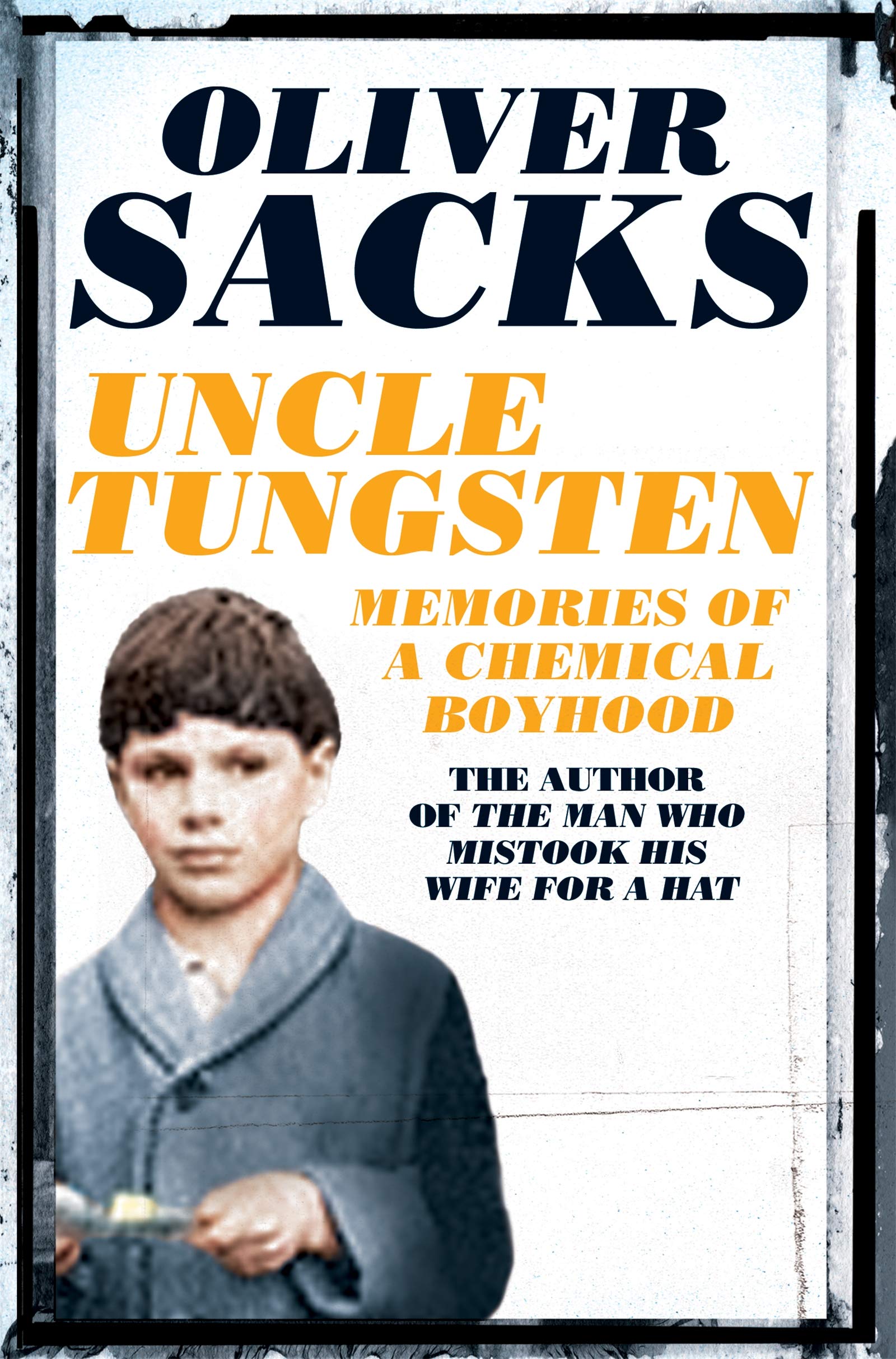

Oliver Sachs, Uncle Tungsten

I really like this biography/science history cross-over. Sachs himself is a fascinating human being, and his enthusiasm for chemistry, dormant for many decades, but reawaken to write this book, is contagious.

- The name of his company was Tungstalite, and they also made crystals for radio receivers.